Hindutva as an ideological force has gained prominence and visibility after 2014 with the election of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to the Centre. Christophe Jaffrelot, in his book Hindu Nationalism: A Reader, comments that Hindu Nationalism emerged from the “superimposition of a religion, a culture, a language, and a sacred territory-the perfect recipe for ethnic nationalism”. Social media helped in transmitting this ideology through the circulation of photos, videos, and posts on different platforms like Facebook, X, Instagram and others. Memes have been used for various purposes ranging from making fun of minorities and criticising the government to educating people by introducing an element of humour in the learning process. They have been defined by Mrinal Pande as “characterized by strategic features such as fads,… remixes,…and images that may be altered, modified and/or shared by users”.

I was surfing Instagram one day and came across a meme page titled “hindu.meme.dal”. At the outset, the range of ideas portrayed through the memes made little sense but on careful inspection, three recurrent themes emerged: a glorification of Hindu beliefs and traditions; projection of non-Hindus as the ‘other’ and not belonging to India and denigration of women by creating binaries of modern and traditional. This article will attempt to read one meme from each of these themes and show how they contribute to the ideology of Hindutva.

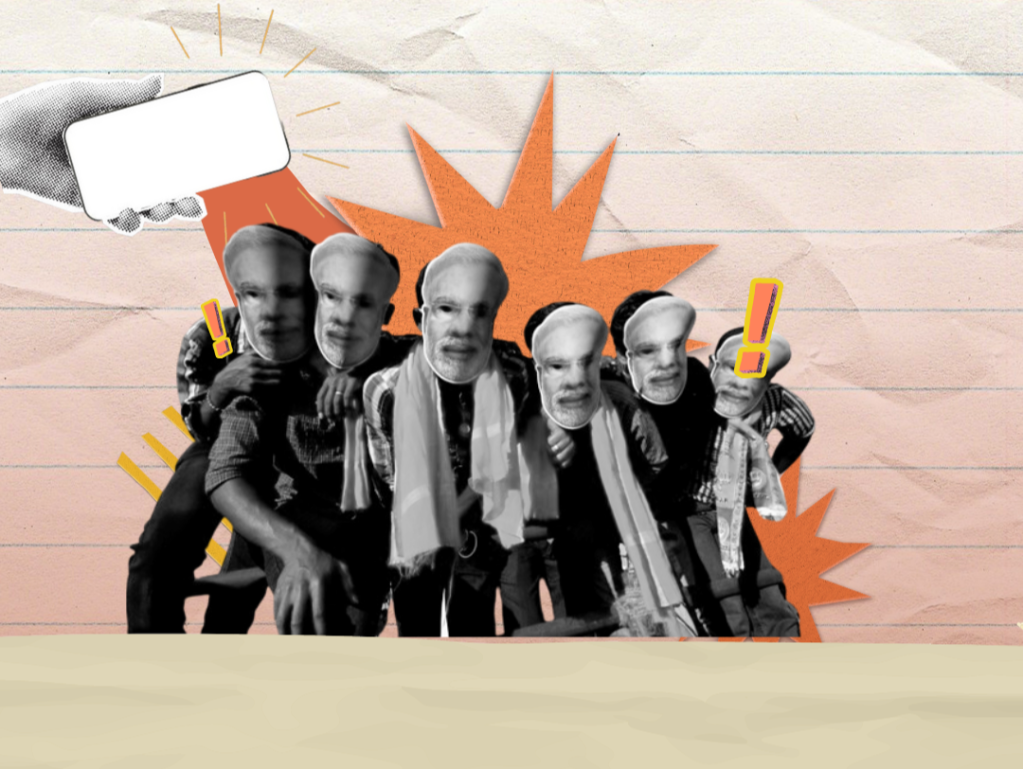

The majority of memes turned out to be promoting the glorification of Hindu traditions. The visual appeal coupled with the short messages in memes served as conduits for convincing people to accept them as a part of their culture and created a “feeling of we”. A well-known strategy employed by the creators of memes was using the pictures of celebrities in them. Their familiarity with viewers was used to drive up engagement rates and induced a perception that their idols were endorsing the message suggested in the memes.

In Figure 1, we see Indian cricketer Virat Kohli holding the energy drink Boost in his hand. At the top of the meme, a verse of Hanuman Chalisa is written that translates into: “Chanting the name of the brave Hanuman defeats illness and alleviates suffering.” The meme sends out the message that Kohli’s belief in Lord Hanuman gives him the energy and motivation to play cricket. A tilak is also added to Kohli’s forehead to complete his transformation from an Indian sportsman to a Hindu sportsman. Being the former captain of the Indian men’s cricket team and a youth icon, the cricketer’s image functions as a good endorsement for promoting a particular brand of religious nationalism.

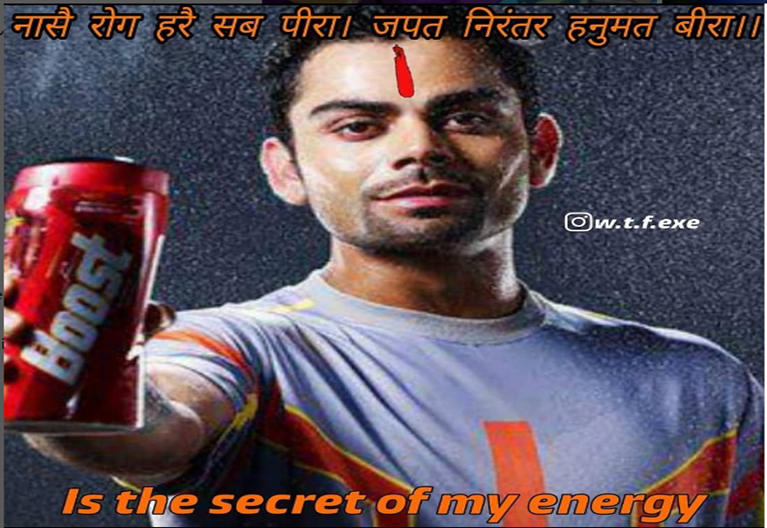

In contemporary times, the Central Government through various measures like the abrogation of Article 370, bringing in the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, and letting the perpetrators of lynching against Muslims go scott-free has emerged as the icon of Hindutva. An identical strategy of manipulating the capability of celebrities to influence people was employed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) during the Group of 20 (G20) leaders’ summit in 2023. It is interesting to observe the narratives created around the hosting of the event by India. The rotational basis of the presidency every year, which enabled the country to host it, was turned into a personal achievement deriving from the aura of our Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. The dazzling spectacle manufactured around Modi completely obscured the tactic employed by the incumbent government to exchange presidency with Indonesia in 2022 so that the routine event could be proclaimed as a masterstroke in foreign policy and used to reap electoral benefits in the 2024 General Elections.

To accentuate the notion of India being respected worldwide for its diplomatic prowess and leading the world in framing solutions for some pressing issues plaguing it, sportspersons were roped in for endorsement. The Indian badminton player, P.V. Sindhu commented on X (formerly Twitter) that the world experienced the “dawn of a resurgent India” under the stewardship of Modi. Thus, we can see how ideals of national pride get propagated through covert distortions of images and with the tacit approval of celebrities. As already established, this shameless glorification of Modi gives credence to his image of nationalism as being essentially religious in nature and leads to its dissemination among the masses.

The second most common theme that came across was the ‘otherisation’ of non-Hindu people. The best way to strengthen the feeling of identitarian cohesion among viewers is to find an outlet for their pent-up hatred. An ‘other’ is constructed as a scapegoat for this purpose and accused of being not only different from Hindus but also obstructing the formation of a Hindu Rashtra.

In Figure 2, we see three people, wearing skullcaps and holding the Indian national flag, running apparently to prove their loyalty to the nation by posting multiple updates on their social media accounts on Republic Day. This template has also been borrowed from a hilarious moment in the Bollywood movie, Phir Hera Pheri (2006), where everyone is seen running after the two black bags filled with money. The hilarity is retained by the meme and two things have been photoshopped- the national flag and skull caps. In contemporary India, hyper-nationalism is promoted by the incumbent Central government and Muslims are told to be grateful to the nation for providing them refuge in a Hindu Rashtra by proving their patriotism through the circulation of social media posts on national events. Usually, Hindus can be seen demonstrating their love for the nation through multiple social media posts on Republic Day.

In the memes, it is interesting to observe how Muslims have been accused of doing so and even mocked for attempting such a performance of patriotism. This exercise not only re-enforces the notion of Muslims posing as nationalists on certain occasions but also solidifies the position of Hindus as being the ‘real’ patriots. The careless way of including the flags in the image disturbs the aesthetic appeal and fits the narrative of Muslims being unfit to be flag-bearers of nationalism. The rapid motion of the characters depicts the intense level of anxiety faced by Muslims in the face of burgeoning discourses of Hindutva. In order to avoid attaching the label of ‘anti-national’ to their identity, Muslims are forced to participate in the performance of aggressive nationalism. It is this fear of Muslims that is used in the meme as a humorous element.

Besides memes, different strategies have been deployed by bigots to harass religious minorities in online spaces. In 2021, an app named ‘Bulli Bai’ was created by “Trads” (Traditionalists), an online far-right group having Nazi sympathies which called for the genocide of Indian minorities. Through that app, images of Muslim journalists and activists were circulated and a mock auction was conducted which depicted women as commodities. Although the app had been taken down and the police had accosted the creators of the app, it is difficult to erase the traces of horror left behind in the aftermath of this incident. This is evident in the disturbing anxieties circulating a victim’s mind: “hate crimes against women don’t end with just murder. It’s harassment, molestation, rape, torture, and then if you get lucky, then murdered”.

The third theme depicted the use of women’s bodies and behaviour as sites for imprinting ideals of nationalism.

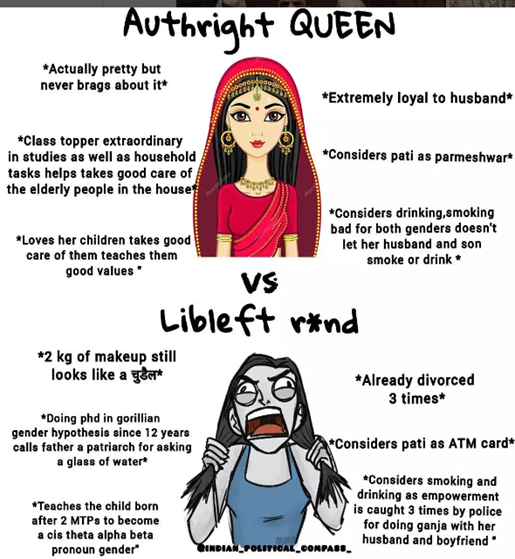

In Figure 3, we see a comparison between women, wherein one of them is seen bedecked in jewellery, wearing ghoonghat donned by Hindus and looking in a composed manner, and another cross-eyed woman is seen holding her hair with her mouth wide open in a state of frustration. The qualities attributed to the ‘Authright Queen’ indicate that she is docile and upholds patriarchal traditions whereas the woman at the bottom is a liberal and has leftist leanings by protesting and being unsubmissive to patriarchy. What naturally is sought to be extended and established from this situation is that only a husband can accord a woman respect in society. Sacrificing her life at the altar of her husband earns the ‘traditional’ woman the epithet of “queen” and this glorification is earned at the expense of relinquishing her freedom and desires. People espousing ideals falling under the broad umbrella of ‘liberals and leftists’ have always been abused by Hindutva sympathisers for criticising the conservative ideas of the latter.

It is no wonder that the identity of the ‘modern’ woman is a portmanteau which has been created from the two different ideologies and linked with an expletive just based on their hatred for religious fanaticism. Words like “cis theta alpha beta pronoun gender” are gibberish and mock the adoption of specific pronouns by queer individuals. This is pitted against raising a child according to normative gender conventions and is seen as contributing to the development of an Indian family. Situating heteronormative family at the centre of Indian nationalism, memes can bestow the status of a citizen to ‘traditional’ women and brand queer ‘modern’ individuals as ‘outsiders’ misguided by foreign influence.

According to Partha Chatterjee, in mid-nineteenth century Bengal, to counter the technological progress achieved by the Western colonisers, spirituality was asserted to be a domain wherein the East was unparalleled. The binary of home and world was constructed which placed women as the custodian of the former realm and had to be protected in the interest of the nation. Nationalism helped in the entrenchment of patriarchy by positing Western/’modern’ women as engrossed in material pleasures and Eastern/’traditional’ women thinking about the “well-being of the home”. It is evident that the conservative spirit that animated the discourses around nationalism in the nineteenth century continues to exist in modern-day India.

In the age of shortening attention spans, memes have the unique ability to attract viewers through small texts and carefully chosen images which attest to and strengthen their inherent cultural prejudices. This characteristic, aligned with the ease with which memes can be created, makes them the perfect medium for the circulation of propaganda among the masses. In such a politically charged climate, it becomes imperative to set forth a counter-narrative to check the infusion of such poisonous ideologies in society. A serious engagement with memes and not brushing them away as merely being products of entertainment can help in a better understanding of the Hindutva forces at play in our society. The creation of memes which offer a secular imagination of India could be one possible way, among many others, to check the proliferation of hatred. Despite the hegemony of Hindutva memes in digital spaces, this step could go a long way in initiating discussions on the pitfalls of constructing India along the template of a Hindu Rashtra.

Supratik Sinha is a postgraduate student of English at Shiv Nadar University, Delhi-NCR.