Since the first printed newspapers appeared in Germany in the early 17th century, brutal repressive regimes of state censorship were up in arms to suppress them. During the tumultuous decades of the English Revolution, the radical press thrived but was nonetheless undermined by the Printing Acts of 1662. The radical enthusiasm was carried through revolutionary France and Jacobin England in the 18th century (the latter also oversaw new standards in provincial journalism). When censorship laws looked toothless, the budding capitalist nation-state responded with its most potent weapon — co-optation. The bourgeoisie civil society of the 19th century gave rise to a very particular kind of ‘daily’ that would parrot the voice of the bourgeois state itself.

However, between 1815 and 1840, the working masses of England, enthused by the Chartists, launched an unprecedented campaign for the freedom of the press — a struggle that would be termed a ‘war for the unstamped.’ Against the ideas championed by the likes of Carlyle, the working-class dailies published poetry, spread their own popular culture and religious sentiments, and, above all, published low-cost editions of passages from Byron, Shelley, Voltaire, and Cartwright, thereby playing a pivotal role in fomenting radical class consciousness. Away from Europe, in the colonies, many such dailies played a significant role in forging an anti-colonial awareness. Communist party dailies worldwide during the 20th century would inherit the mantle of this insurgent radicalism.

The reason for recounting this history was a chance encounter with a stash of antique newspapers covering a period of ten years. A treasure trove tucked away casually in National Library, Kolkata and the dilapidated Ganashakti Library of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Kolkata — these newspapers reveal the intellectual vigour of working-class and peasant organizations as they mounted a serious challenge to the late-colonial state and a fledgling post-colonial polity. However, these intrepid tales of the imaginative faculty of people seldom made their way into the mainstream print media. To illustrate this, I start by comparing news reports published in Swadhinota (the then official mouthpiece of the undivided Communist Party) and Anandabazar Patrika (the alter-bearer of the Bengali public sphere and the representative of the pro-Congress elite of West Bengal) during the first two months of 1954. To the lay reader and also to the trained historian, 1954 apparently shall ring no bell. It is not regarded, and rightly so in the annals of history, either as a year of great tragedy or of immense comedy. So are the first two months of the year.

The mundanity of the times was aptly captured in the editions of Anandabazar. Having to report nothing of note, their editorials were vague — with occasional speculations surrounding the chances of Netaji’s survival and intermittent reflections upon the economy of the republic. At times, the monotony gave way to the search for a hero. The hero was eventually found in Nehru, who had set out to carve a place for India on the international map. The man and his party assumed the image of the polity itself, as a grand convention of the Congress party was held at Kalyani in West Bengal. The small suburb town would be called Congress Nogori (Town of the Congressmen) — as working-committee resolutions would be churned out to educate its lay workers of their duties to the nation. From the podium, amidst countless spectacles, Nehru was to launch India into modernity. A modern India would also grow into being the beacon of peace for a war-torn world, devastated by American bombs, across Korea to Vietnam. His daily activities and ideas reverberated in innumerable editorials and post-editorials as the nation tried to find its feet in modern science, technology, and agriculture.

For some unexplained reason, the news of Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Gibraltar took center stage in the edition published on 19th January. Equally puzzling for a daily seeking to cast the newly independent polity in the mould of modernity were the extensive coverages of Kumbh Mela, and activities at Belur Math. A weekly column dedicated to women would encourage them to be educated and well-informed, but only in culinary and sewing skills — certainly not very befitting for an emerging public sphere. One can sense the insecurities of the nascent nation-state on the pages of Anandabazar, evident in suspicious reports of bilateral security deals between the USA and Pakistan on the front pages. However, the idea of Bengal and its cultural pride would always be distinct from that of India as a whole. The sense of Bengalis being robbed of their rightful position of dominance in Indian politics found its expression through Subhas Chandra Bose, and his conflicts with Nehru and Gandhi. Every now and then, Anandabazar would speculate on the whereabouts of Subhas Chandra Bose and how he might come back one day to save the nation. Despite all the enthusiasm for Nehru, he could never become a person who would capture the imagination of the Bengalis. That place was reserved for Subhas Chandra Bose — who, if alive, was believed to have been able to avert the tragedy of Partition.

Anandabazar recorded the story of an aspiring nation in its vaguely titled editorials such as Arthonitir Ek Bochor (One Year of the Economy) and Projatontrer Dui Bochor (Two Years since the Birth of the Republic). However, dreamers were left out of the dream. It drowned out the voices of many who would make their way into the tiny columns in Swadhinota. If these voices are paid the attention they deserve, the first two months of 1954 might not appear so banal and unremarkable. The edition published on the 4th of January would open with reports from two different corners of the world — one from Iran and the other from Vietnam. An unnamed reporter reported on massive student-led demonstrations against the British-led coup that toppled Mossadegh the previous year. The information from Vietnam would read of the Vietminh’s gains at Dien Bien Phu (the famous battle would only be fought two months later) and Saigon.

On the 11th of the same month, Swadhinota reported on a spontaneous strike (not led by the trade unions) at a paper mill in Titagarh. Fascinating is its consistent coverage of an incident wherein three coal workers’ union leaders were sentenced to death. The reports were first published on the 23rd of January, then again on the 4th and 5th of February. On the 18th of February, a petition was submitted to commute the sentence. The last mention of the incident can be found on the 14th of March. However, the sorry condition of these records does not allow us to ascertain the final outcome. Nor is it clear what provoked such aggressive action on part of the courts. They probably had crossed the limits of trade unionism that the post-colonial polity allowed — when they questioned the British ownership of a not-so-heard-of coal mine in Bihar (something along these lines was first published on the 4th of January).

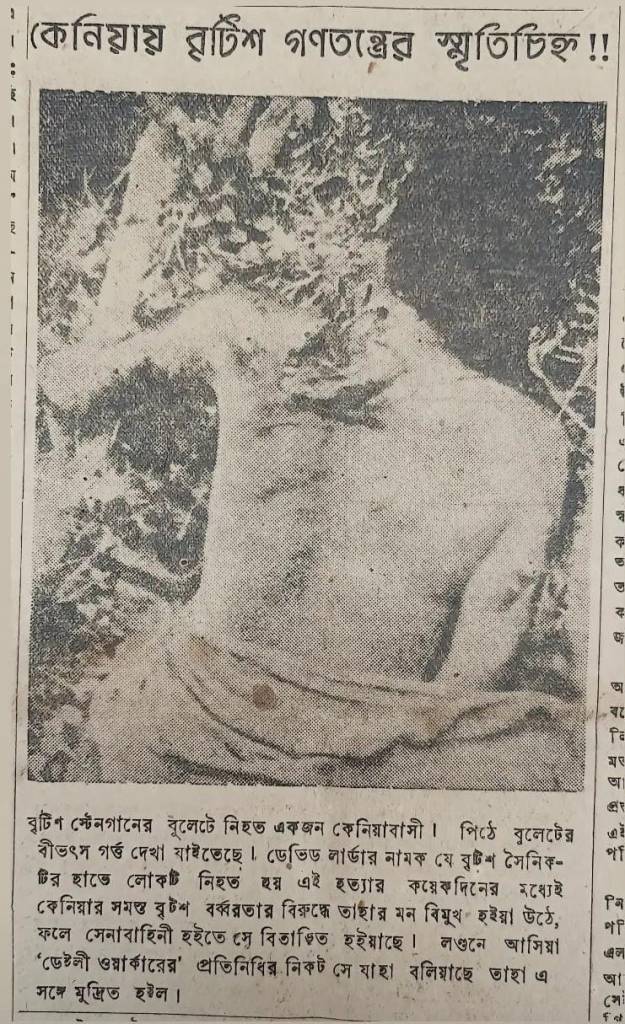

Interspersed among all these were the coverages of the ensuing Teachers’ and Refugee Rehabilitation movement in West Bengal, the Movement for National Liberation in British Guyana, the Mau-Mau Rebellion in Kenya, and the war in Indo-China. The efforts of all the unnamed reporters — who attempted to re-inscribe the unwritten — is beyond all praise. The times were far from mundane if viewed from the perspective of the underlings of the society. Beneath the calm, history was being made; and dailies like Swadhinota would make an attempt to record the actions of all those who resisted, struggled, and questioned.

The professional curation of Swadhinota would enable it to achieve more than straightforward reportage. It is not that Swadhinota had reporters worldwide. Instead, they would collate and translate ground reports published in newspapers worldwide. Hence, one would also read reportages from dailies published in Africa, Europe, and Latin America on its pages. The editorials and advertisements bore evidence of a great deal of prior planning. The content they could churn out in their editorials and unique columns deserves careful reading. These would provide incisive theoretical explanations of events rocking the world at that moment by breaking down for the lay reader concepts like nationalism, brotherhood, internationalism, fraternity, patriotism, and imperialism.

Most importantly, one must acknowledge their contribution to the literary ephemera of Bengal. Translations of obscure poems and prose from across the world, publications of songs and artwork that struggled to find a home elsewhere for their radical tenor, and thought-provoking essays form a rich repertoire of texts which lie in obscurity today. An entire page was dedicated to the translation of world literature. It is difficult to imagine that poets like Paul Elluard, Louis Aragon, and Martin Carter would find a place for themselves in Bengali minds as early as in 1954. Another weekly page was published that only contained essays on women’s mobilization, from the times of the Suffragettes to the present. Indeed, a public sphere was imagined where all would have a say. A national imagination of a very different kind was advocated. Away from the nationalistic drum beats and jingoistic chest-thumping, these pages encapsulated the aspirations of a dreaming population. A people who dreamt of a world better than the one they inhabited.

One should say that the Communist Party dailies of the day were never merely party mouthpieces. On the contrary, they transcended petty party politics. They would grow into being the mouthpieces of the people. Most importantly, they would leave an unmissable imprint on the public sphere of the place. Almost seventy years later, we stand at a time when mainstream press is dead. Alternative journalism suffers from a lack of resources and ideas. Those who manage to break the shackles of constraints eventually are meant to face the predicament of NewsClick. This incoherent jumbling of thoughts is meant to serve as a reminder for the need to explore possible avenues for innovative journalism. The strikes, lock-outs, and shutdowns seldom feature in today’s press coverage. The reader, too, is reduced to a state of passive acquiescence. Today’s newspapers can seldom make one’s blood boil — as the oppressed stand eradicated from international news, and even worse, are held accountable for voicing their yearning for liberation. It is time that we look back to the past for renewed inspiration.

All photographs by Rajarshi Adhikary, courtesy Ganashakti Library, Kolkata, and National Library, Kolkata.

This is an extraordinary piece. I’m so enthralled by the writing that it makes me realize about the necessity of digging the past, the history…..the logical appeal presented in the article and its tone both are impressive.

LikeLike