“In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible…Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.”

–––George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

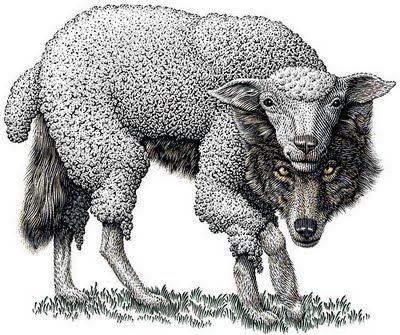

The much-touted National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) is here. It has been approved by the Cabinet and its arrival has been triumphantly announced by the Indian media in a manner that would put to shame the finest quality of man’s best friend. The NEP is a clever document. It is ambiguously worded and mostly vacuous in content. However, it is not without its share of dazzling promises. The NEP seeks to transform the education sector of the country through greater emphasis on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), expansion of the ambit of the RTE, a shift towards continuous evaluation, establishment of an Indian Institute of Translation and Interpretation, and by doing away with the rigid trifurcation of streams into Science, Commerce, and the Humanities. Yet, this rosy picture diverts our attention from the pernicious pitfalls that punctuate the NEP. It speaks in a tongue that is fabulously forked. A cursory glance at the document gives the impression that it is the perfect vehicle to bring about the promised metamorphosis. A close reading, on the other hand, makes one realize that the NEP is not the chrysalis of a beautiful butterfly but the cocoon of a miserable moth.

The NEP proposes to extend the mid-day meal programme “to the Preparatory Classes in primary schools” (1.6) and also provide them with breakfast. On the face of it, this seems to be a fantastic idea. On probing deeper, one discovers that the NEP is conspicuously silent on the fate of the mid-day meal programme at the middle school level. Reallocating government expenditure for the mid-day meal programme, instead of increasing it, creates an illusion of change at one level while paving the way for cutting costs at another. The NEP seems to be fascinated by the prospect of “trained volunteers – from both the local community and beyond –[participating] in this large-scale mission [of attaining universal foundational literacy and numeracy]” (2.7). One cannot discount the possibility of RSS pracharaks masquerading as self-proclaimed ‘social workers’ and infiltrating the lowest rungs of the school education system on this pretext. The NEP seeks to “allow alternative models of education” by making “the requirements for [them] less restrictive” (3.6). Without ensuring greater regulation and accountability (as is done at present by the State Madrasa Education Boards), the NEP makes an attempt to justify the mushrooming of these ‘alternative’ institutions which do not always function transparently enough.

The NEP encourages interdisciplinary studies from the school level onwards. Students can now choose to study any combination of subjects irrespective of the three streams into which these were previously classified. Strangely, however, the policymakers are under the delusion that these “purely curricular and pedagogical” changes will not entail “parallel changes to physical infrastructure” (4.3). At the very basic level, since it will now become impossible for schools to group students into the rigid sections of Science, Commerce, and the Humanities, provisions have to be made for at least increasing the number of classrooms, without which this freedom of choice will remain available only on paper. “Curriculum content will be reduced in each subject to its core essentials,” (4.5) announces the NEP with great optimism. Recently, we witnessed the CBSE reducing its syllabi in order to attune them to the COVID 19-impacted academic year. For the social sciences, this meant sanitizing the curriculum of those topics (secularism, caste etc.) that are most unpalatable to the present ruling dispensation. There is ample basis for fearing misuse of this provision of the NEP.

Inspired by the idea of digital education and environmental consciousness, the NEP states: “Access to downloadable and printable version of all textbooks will be provided by all States/UTs and NCERT to help conserve the environment and reduce the logistical burden” (4.32). Yet, it does not dwell much on how these digital aids to school education will be made universally accessible and inclusive across the length and breadth of the country. Those who cannot access digital resources for education must fend for themselves. The NEP simply does not care. Contradicting its own idea of decentring board exams by means of continuous assessment and options for improvement, it proposes undergraduate and graduate admissions through even more centralized common entrance exams administered by the NTA. This is supposed to “drastically [reduce] the burden on students, universities and colleges, and the entire education system” (4.42). This idea is fraught with problems—logistical and otherwise. To homogenize admissions across the country is to disregard the distinct and diverse eligibility requirements for specialized courses in institutions that have over time carved out their own niches, and have administered admissions in a fair and time-tested manner till date. The NEP hopes against all hope that the NTA will somehow be able to replace such mechanisms by waving a magic wand which it does not seem to possess at the moment.

The NEP’s most inconsiderate idea with regard to school education is couched in deceptive jargon. It notes with great concern that “small school sizes have made it economically suboptimal and operationally complex to run good schools, in terms of deployment of teachers as well as the provision of critical physical resources” (7.2). To resolve this, it goes back to one of the earliest education policies after independence: “the establishment of a grouping structure called the school complex, consisting of one secondary school together with all other schools offering lower grades in its neighbourhood including Anganwadis, in a radius of five to ten kilometers,” as was first enunciated by “the Education Commission (1964–66) but was left unimplemented.” The NEP “strongly endorses the idea of the school complex/cluster, wherever possible,” (7.6) under the cunning euphemism: “rationalization of schools” (5.10). In other words, the NEP wishes to do away with the problem of unfeasibly small schools not by injecting more public funds to make them well equipped, better staffed, and operationally viable, but by coat-tailing many such schools in a large area to a singular complex/cluster. The NEP is not so concerned with the challenges of increasing accessibility to and the resources of small schools in remote areas as it is with cutting costs by shutting them down altogether. Let the children walk for miles to reach the nearest complex/cluster – the NEP couldn’t have cared less. Education is an entitlement for a few and an unattainable privilege for many.

When it comes to higher education, the NEP swears by the talismanic authority of multidisciplinarity. It envisions that all Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) will in a decade or so evolve into “large multidisciplinary universities and HEI clusters,” with programmes across disciplines and fields (10.2). All HEIs must necessarily become jacks of all trades no matter what their current focal interests or research niches are. There is absolutely no rationale in the document to justify why all Indian HEIs should follow this ‘multidisciplinary’ trajectory in such a blinkered manner. “By 2040, all higher education institutions (HEIs) shall aim to become multidisciplinary institutions and shall aim to have larger student enrolments preferably in the thousands, for optimal use of infrastructure and resources, and for the creation of vibrant multidisciplinary communities” (10.7) decrees the NEP while implicitly discouraging the establishment of any new stand-alone institutions or smaller academic centres. Can we expect the Deccan College to start courses in fashion technology? Will the Madras School of Economics offer undergraduate degrees in comparative literature? Can Visva Bharati churn out MBAs à la the IIMs. Should the FTII think of hiring faculty with expertise in theoretical Physics? The NEP does not provide concrete answers to any of these questions but it is of the opinion that all HEIs should compulsively try their luck at everything and hope that it all works out fine for them.

The NEP postulates that by 2035, “[a]ll colleges currently affiliated to a university shall attain the required benchmarks [so as to] eventually become autonomous degree-granting colleges…through a concerted national effort” (10.12). This apparently innocuous proposal is another way of saying that all colleges across the country, irrespective of their geographical location, present infrastructure, size of faculty, and availability of funds should somehow scramble towards a hallowed ‘self-governance’ that they probably will not achieve and most certainly cannot afford. The NEP aspires to replace “[t]he present complex nomenclature of HEIs in the country as ‘deemed to be university’, ‘affiliating university’, ‘affiliating technical university’, ‘unitary university’” by the more simplified and ubiquitous term: ‘university’ alone (10.14). It does not bother exploring why this varied terminology came to be used in the first place before advocating a one-size-fits-all approach. The NEP refuses to acknowledge the diversity intrinsic to the chequered landscape of higher education in India. In its pursuit of a chimeric ‘multidisciplinarity’, it invents some terms (like “Multidisciplinary Education and Research Universities” or MERUs) and obliviates others without paying any heed to their present relevance or past context.

“The M.Phil. programme shall be discontinued,” (11.10) says the NEP, without commenting on the future of the students who have recently obtained that degree or are presently enrolled in courses that will enable them to obtain it, across the country. The most misleading euphemism in the document, however, is to be found in this provision: “[t]he undergraduate degree will be of either 3-or 4-year duration, with multiple exit options within this period, with appropriate certifications” (11.9). It is but a clever way of masking statistics that show the ugly truth of college drop-outs in the country. This is a known ploy. When farmer suicides were hitting the news headlines, the government had chosen to recategorize such deaths as under a column called ‘other’ in the National Crime Records Bureau reports. Unwilling to provide the necessary support and safety nets to students who are forced to discontinue their pursuit of higher education, the NEP has discovered the fanciful phrase “multiple exit options” to provide less fortunate students with worthless certificates/diplomas which will not just be a reminder of their incomplete education but shall bear testimony to a fundamentally broken system. Many women who dare to dream beyond school education in India will now find these “multiple exit options” to be the fast-track avenues for their families to marry them off before they could complete their degrees. Barring the elites, college drop-outs are expected to look forward to uncertain futures as quarter/semi/almost graduates.

To fulfil its obsession of propping India up as the ‘Viswa Guru’ in the field of higher education, the NEP will permit “selected universities e.g., those from among the top 100 universities in the world…to operate in India” in a totally unfettered manner (12.8). The crème de la crème of the country will now get to send their children to the neighbourhood campuses of Oxbridge and Ivy Leagues—a special service brokered by the NEP exclusively for elite consumption. “Students are the prime stakeholders in the education system,” (12.9) concedes the NEP magnanimously. Yet, this statement parodies itself. In the past few years alone, existing student unions have been derecognized, student protests stifled, dissent criminalized, student representation side-lined, committees against sexual harassment disempowered, and elected student leaders intimidated, harassed, and detained for giving voice to legitimate demands. Quite expectedly, the NEP does not even pay lip-service to the demand for greater student involvement in decision-making processes—it remains cunningly silent on this matter.

Among other vague claims, the NEP states that “‘Lok Vidya,’ i.e., important vocational knowledge developed in India, will be made accessible to students through integration into vocational education courses” (16.5). It does not bother to clarify what would fall under this undefined category of ‘Lok Vidya’. Given the track-record of the first NDA government (1998-2004) and the agenda it had pushed in the sphere of education, it will not be surprising if the new Education Ministry seeks to peddle and legitimize pseudoscientific garbage masked as ‘Lok Vidya’. Earlier, the present HRD minister had made no secret of his undiluted admiration for astrology in the Parliament. We should be very wary. Another proposal of the NEP gives further credence to this suspicion: “all students of allopathic medical education must have a basic understanding of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH), and vice versa” (20.5). This is a recipe for disaster. Why will trained doctors be expected to learn about alternative medicine when the Medical Council of India forbids them to prescribe anything other than allopathic drugs? There is also a Supreme Court judgement preventing cross-practice by quacks. However, a highly controversial bill moved by the government in the Parliament seeks to enable AYUSH practitioners to prescribe allopathic drugs to their patients after completing a ‘short-term bridge course’. The NEP seeks to buttress this idea. Its provision can open the floodgates for apparently justified cross practicing in India by people without possessing required qualifications, training, or expertise in medical science.

The NEP has also proposed the setting up of a National Research Foundation (NRF) “to enable a culture of research to permeate through our universities” (17.9). What does this vague phrasing even mean? If viewed in the context of repeated remarks made by leaders of the ruling party calling for defunding all research (mostly in the humanities and the social sciences) at ‘anti-national’ universities that do not conform to or serve their ideological purpose, this can mean only one thing: greater surveillance. Authoritarian regimes are obsessed with ‘coordination’ in the same way Nazi Germany was with Gleichschaltung—in academic research this implies thought-policing. In order to curb “heavy-handed[ness]” (18.1) in the regulation of higher education, the NEP, in a patently contradictory move proposes even greater centralization through “four independent verticals within one umbrella institution, the Higher Education Council of India (HECI)” (18.2): “a common, single-point regulator,” (18.3) the National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC); “a ‘meta-accrediting body’,” (18.4) called the National Accreditation Council (NAC); a “Higher Education Grants Council (HEGC)” (18.5); and a “General Education Council (GEC)” (18.6). The present inefficient regulatory regime, which has led to the accumulation of too much power in too few hands is sought to be replaced by a system which will only perpetuate the problem at best and exacerbate it at worst.

This “system architecture” (18.8) is expected to empower HEIs to move towards “graded autonomy in a phased manner” (19.2). Academic autonomy is that carrot which is perpetually promised but never granted. Financial autonomy is that stick with which the government wishes to beat the public education system black and blue, paving the way for private players to capture the higher education market in India. The NEP refuses to distinguish between public and private HEIs, enabling the latter to extract profits while the former face a serious possibility of cost-cutting. In a third-world country like India, the Public Private Partnership (PPP) model is one that has already been tried but has not succeeded. The private investors here in most cases are not extremely generous alumni or charitable trusts but profit-oriented firms intending to diversify their business. For example, IIIT Guwahati, among other institutions, had been established following a PPP model and has been plagued by administrative conflicts and funding problems almost since its inception. The NEP plans to “empower the private HEIs to set fees for their programmes independently…[they] will be encouraged to offer freeships and scholarships in significant numbers to their students” (18.14). In a country, where the vast majority of students could not have pursued higher degrees had it not been for the state-funded public education system, this proposal is not just outrageous, it is obscene. Instead of putting a cap on the fees that existing private HEIs charge from their students, the NEP is opening up the education sector for even greater commercialization. It assumes an anti-commercialization rhetoric for the purpose of deceiving students, while giving a free hand to big business to charge as they will and reap exponentially more than what they sow.

The NEP is a difficult document to read. It obscures more than it reveals. It plays with and on words to surreptitiously push through an agenda in the domain of education which is fundamentally anti-people in nature. It subordinates the interests of students to those of private players. It promises to be revolutionary, but ends up being reactionary. It is the opposite of what a good education policy should be like. The makers of this policy know this only too well. This is precisely why they have masked its shortcomings and sly propositions in a deceptively innocuous language, and pushed it through the cabinet, bypassing the legislature and the state governments, and without much consultation with the primary stakeholders. An education policy conceived in such an undemocratic manner and embodying the principles of cost-cutting and privatization cannot fool people for long. Its promise of allocating 6% of the GDP for the Education sector is meaningless because GDP subsumes private investment. What is required is the earmarking of one-tenth of the budgetary expenditure for the sustenance of a robust public education system in the country. That does not seem to be forthcoming. The NEP is a strange document. Its façade of linguistic elegance desperately tries to hide its sinister implications. We must not be fooled by its sugar-coated lies. The sheep’s wool cannot cover the wolf’s fangs, no matter how hard it tries.

One thought on “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: The Pernicious Pitfalls of the New Education Policy—Suchintan Das”