In late February 2025, as the disruptive policy orders of US President Donald Trump were generating their cascading effects globally, India’s first three clinics directed towards transgender people faced an unforeseen closure. Located in Hyderabad, Pune and Kalyan, these clinics faced the tightening of funding caused by the halting of USAID, the word that has been salient since. Expectedly, the abrupt and complete squeeze of US state funding for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) — the overseas aid agency of USA — has created a pall of uncertainty and despair across the global social sector, from hospitals to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) now grappling with survival questions. While spawning shock and dismay, it was in keeping with the larger pattern of radical slashing down of government functions – and spending – in the ‘shock and awe’ approach that has come to signify the Trump governance in the brief first quarter of 2025. The move, projected as a purge of inefficiency and misfit with American interests, has ripples that extend far beyond mere budgetary readjustment and downsizing. It constitutes a historical rupture, effectively reversing and exposing the fragile facade of neoliberal global aid while raising questions about the resilience of social welfare systems globally, as well as the shifting tectonics of capitalist power. In a world already beset by a multitude of overlapping crises — pandemic aftershocks, geopolitical turmoil, and climate-induced disruptions — this retreat also lays bare the contradictions and pitfalls of interdependence, a concept once celebrated as the epitome of globalisation but now tottering under the weight of crude unilateralism.

Launched in 1961 during J.F. Kennedy’s zealous Cold War push, USAID started as a massive soft-power instrument, pouring billions into countering Soviet influence. By the 1980s and ‘90s, as neoliberal ideas like the Washington Consensus gained salience, USAID’s focus changed. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation became the dominant policy prescriptions that swept nations, and venerated the supposed supremacy of the Western neoliberal capitalist model. While history certainly did not end –- with newer and more lethal inequalities, wars on terror and amplified climate change –- the much less salient phenomenon that gained ground was the diffuse but concerted weakening of state-led welfarism in non-’developed’ nations and the filling of that gap by NGOs, aid organisations, charitable foundations, etc. To illustrate, the USAID-Kenya portfolio was designed in a way that only a minimum of funds were channelled through the Government. The programme worked primarily with nongovernmental organisations and the private sector. Ironically, the global war on terror, regime changes, and military-industrial complex brought devastation to those very countries that the West had framed as a thirsty ground clamouring for aid-led upliftment. From Iraq to Afghanistan, the wreckage and subsequent US-aided ‘reconstruction’ ensued almost as if it were a pre-ordained sequence. A decisive de-centring of the narrative focus away from crumbling state welfarism thus ensued.

Mark Duffield’s works, like Development, Security and Unending War and Post-Humanitarianism: Governing Precarity in the Digital World, demonstrate how the rise of NGOs and private contractors in aid delivery since the 1980s has reconfigured humanitarianism. This shift, visible in cases such as Sudan’s “fantastic invasion” of NGOs during the mid-1980s drought, transformed humanitarian action into a system for managing precarity in the Global South instead of driving structural change. Instead of building robust state-led welfare systems or tackling systemic economic disparities, aid systems prioritised immediate interventions that maintained a state of minimal survival. This involved providing temporary relief (e.g., food aid, basic healthcare) to keep crises at bay, thereby containing instability and vulnerability. Duffield particularly examines the “security-development nexus,” where aid aligns with Western security interests, and analyses how humanitarianism becomes politicised through UN “integrated missions” that merge aid with political and military goals. A concrete example of the “security-development nexus” is the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and its enmeshment with USAID-funded programs in the 2000s. UNAMA, established in 2002, operated as an “integrated mission,” blending humanitarian aid with political and military objectives to ‘stabilise’ Afghanistan in the post-Taliban aftermath.

This outcome was by no means accidental. By funding NGOs to address issues like hunger and illiteracy rather than underlying concerns, USAID blunted their political edge, turning them into essentially technical service providers focusing on immediate and recurring relief. It was a shrewd approach to keep subversive ideas at bay, locking aid recipients into a system built on deregulation and private business. The outcome was a dependency that reined in sovereignty without tackling the tougher issues.

The political underpinnings of USAID’s support for NGOs and organisations assumed another distinct avatar –- reshaping and in some cases even superseding civil society in recipient countries. For instance, USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) and Democracy Program funded NGOs and political initiatives in Bolivia, particularly in regions held by separatist movements in arms against President Evo Morales’ government. These programs propped up groups that promoted U.S.-aligned democratic and market-oriented reforms. Local grassroots movements, such as indigenous and peasant organisations supporting Morales’ policies, were slowly sidelined as USAID-backed NGOs gained prominence in shaping and steering the political discourse. As it happened, Morales expelled USAID in 2013, citing interference in Bolivia’s sovereignty and development.

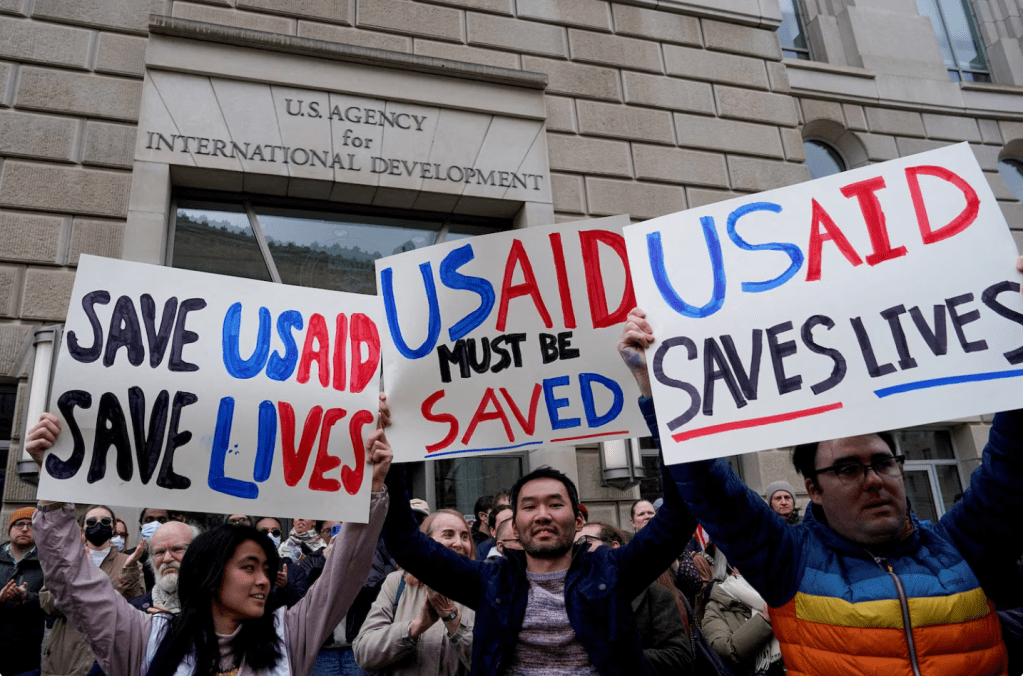

As the US pulls the plug now, the ripples extend far, wide and unexpectedly. The funding freeze and USAID’s downsizing mark a break from the postwar global outlook that created it. Intriguingly, this echoes the pre-World War II isolationism that characterised the US, peeling open the vital question why it took the US 34 years after the demise of the Soviet Union to withdraw from the aid-front of the Cold War? While that merits a separate study in itself, driven by a “my nation first” mindset, and rammed through by Elon Musk and his DOGE’s efficiency push, this shift abandons the soft-power influence USAID once had. Symbolising the confusion gripping the move even after its announcement, Elon Musk threatened that the agency would be shut down, while Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is also now the acting administrator of USAID, remarked about ‘restructuring’ it. At much lower echelons and across shores, the social sector is feeling a sharp and persistent impact. NGOs, ranging from small grassroots groups to large international organisations, face the looming prospect of a severe funding shortage. It is truly the unravelling of support networks built over decades, leaving vulnerable people at the mercy of volatile markets, whimsical ebbs and flows of private donor capital and governments with strained fiscal capacities.

At the micro level, the fallout goes further. Local groups that once counted on USAID funding are now scrambling to adapt, and importantly, their credibility is taking a hit as promises and ongoing programmes crumble. Conversely, the social sector, undergirded by missions to help, is grappling with an ironic impairment: its very reliance on outside support has left it dangerously fragile.

In the longer term, does this signal a new kind of capitalism? Realistically, this shift, for now, suggests a move away from using aid to sustain a U.S.-led global capitalist order, potentially heralding a new phase of capitalism where the U.S. relies less on soft power and more on direct economic and military leverage. This aligns with a broader trend of isolationism, as seen in policies like withdrawing from multilateral agreements (e.g., the Paris Agreement or WHO). It results in a nation looking and pulling inward –- a shift to a more self-centred, deal-based capitalism where national priorities trump global heavy-lifting. Interestingly, this resonates with President Trump’s transactional style of diplomacy which has become starkly acute through the tariffs fiasco. At a broader level, protectionism at home and preaching free trade elsewhere has been a textbook mercantilist tactic. The US is unambiguously taking a similar route, pressuring for free trade arguments or FTAs with developing countries in the narrow ninety-day window for which it has kept tariffs aside. The idea thus far has been to funnel funds through the social impact sector while forcing countries to undertake Structural Adjustment Programmes. Such approaches and mechanisms will certainly take a hit in the current backdrop.

In comparison, China’s approach to development support –- prominently emphasising infrastructure and trade over humanitarian aid –- represents a different model, one less focused on credos of liberal governance and more on state-led economic dominance. While USAID’s aid often came attached with conditions promoting free markets and democracy, China’s investments have primarily prioritised geopolitical leverage and resource access. Pitted against the Western aid-led model that evidently signifies unreliability and possibilities of complete reversal/reconfiguration, the Chinese approach is not without streaks of control but certainly more durable in vision and operation.

Ultimately, USAID’s dramatic retreat marks not just an endpoint, but also a monumental challenge along multiple axes. It exposes the downsides of interdependence and the tentative promise of NGOs shouldering a global welfare net. To be sure, it goes beyond the pitfalls of interdependence, underlining the inevitable breakdown of an overtly US-reliant economic and military architecture that had been taken for granted for far too long. As a result, Europe, for example, now has to think of remilitarisation and bear the costs for the same, decades after it effectively outsourced defence and foreign policy to the US. Within American borders, the gap between economic reality and political grandstanding remains evident – e.g. $71.9 billion in foreign aid that the US Federal government spent in fiscal year 2023 was a paltry 1.2% of that year’s total federal spend of upwards of $6.1 trillion. Whether this leads to a harsher, more divided capitalism or clusters of cooperation led by China and/or the European Union, among others, remains to be seen. For now, the social sector is at a bleak turning point, navigating survival and renewal as the leading actor steps back.