I am an avid user of OTT platforms, utilising the late-night and cheap internet to binge questionable films. As Netflix orients us towards consuming distinct genres, I have been attracted to a peculiar fetish that can only be categorised as Hindutva Cinema.

Films praising the Modi government’s policies have multiplied exponentially in the last ten years. These include those released just before the elections in 2019 — URI: A Surgical Strike which showcases the army’s response to the Pulwama and Balakot Terror attacks. Reflecting on COVID-19 in another instance, the Vaccine War praises the negotiation skills of the scientists from ICMR. Finally, before the 2024 elections came Kashmir Files and Article 370— an expose on the traumatic lives of Kashmiri Pandits and the outstanding bureaucratic achievements of the Indian state.

Fig 1. Poster of Jahangir National University

The genre that has been bastardised and popularly lends itself to Hindutva filmography is the political thriller. This form in the West was used to show the citizen’s power to destabilise the hegemony of the State, as during the Watergate Scandal which resulted in a movie like All the President’s Men. Here, however, Hindutva cinema reframes the citizen journalist or the common soldier in its attempt to affirm state institutions and legitimise jingoism.

My interest amidst all this, as a student of Jahangir National University (termed JNU by many), lies in the changing nature of popular mass culture that these films target and how social media and reel circuits amplify and proliferate these right-wing positions.

The second section of the article delves into the creation of prolific myths and Hindutva fantastical worlds which have been made possible by new technologies like VFX. Finally, the conclusion decodes our compulsive viewing habits and possible solutions at the level of organisation and filmmaking.

The Glamourous Lives of Bollywood

Historically, Bollywood as well as regional cinemas have created a diverse range of audience practices, labelled as a kind of fan bhakti, with its various configurations, sites and cultural practices. Whereas the nationalism of a Mother India (1957) would involve the public sphere awakening to the casting of Nargis Dutt, the daughter of the courtesan Jaddanbai, the 1970s would witness the Angry Young Man typify the struggles of labour, worker’s rights and migration. Further on, the globalised world order would re-imagine diasporic interests in the face of Muslim superstars, Shah Rukh, Aamir and Salman alongside the steady buildup of contraband mafia tensions.

Figure 2. Nargis in Mother India

The kind of public spheres (with its caste/class nexus) that have mobilised verdicts on film stars and movies have been steadily changing. The onset of OTT continues to attract a sanitised environment where the early risk-takers and innovators (creating shows like Paatal Lok or Hindutva sci-fi dystopias like Ghoul and Leila) have dissolved into an apolitical gaze, which is evident, for example, from the censoring of Dibakar Banerjee’s political thriller about a futurist dystopia, Tees. This comes on the heels of a new imagination of censorship laws centred around the Broadcasting Bill which seeks to bring OTT networks and influencers under structured rules and regulations.

On the other hand, hyperreal media events ( which are careful and strategic affective simulations by troll outfits, the press, primetime shows and industry whistleblowers ) continue to intensify around the glamorous lives of Bollywood stars. When Aryan Khan, the son of Shah Rukh Khan, was arrested in October 2021 on the accusation that he had possessed and consumed drugs, a media frenzy erupted and showed the fissures of the relationship between the Centre and the State.

The then Maharashtra minister and Nationalist Congress Party leader Nawab Malik alleged that the NCB’s raid on the cruise was ‘fake’ and the BJP was using central agencies to defame the state. Soon after he was granted bail, one of the NCB zonal directors, Sameer Wankhede, was targeted for allegedly asking for bribes to free Aryan Khan. This clearly showed the fissures of power between the Hindu Nationalist government at the centre, which wanted to utilise its central machinery like NCB and CBI versus the State with its apparatus of the Shiv Sena and Mumbai Police to maintain a grip on the narrative. The drama was being played out in the battleground of Bombay Cinema, as Nivedita Menon has alluded to in one of her articles.1

A steady stream of narratively biased movies is also churned out in regional cinema. Politician-turned-actor Ravi Kishan’s popular masculine image in Bhojpuri cinema is moulded through the mobilisation of right-wing narratives, especially his role as a priest in the movie Hindutva. The rise of Hindutva cinema thus has to be juxtaposed alongside another hegemony — that of an aspirational Brahamanical motivation. This is further coupled with a desirable masculine, in whose ideal image others can be moulded, leading to the proliferation of the daddy biopics — on Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Savarkar and Bal Thackeray, among others. Such a need to create father figures is witnessed in the historical Chhava (2025), which pits and crowns the second ruler of the Maratha Empire, Sambhaji against Aurangzeb.

These media events and narratives which occupy complicated afterlives are disseminated over WhatsApp groups and X(formerly Twitter) accounts like the witch hunt of Rhea Chakraborty after Sushant Singh Rajput’s suicide as well as the mobilisation of Karni Sena around a dream sequence in the movie Padmavaat. These affective relationships and debates that are banally played out linger on at our dinner tables, creating real, credible impacts which can suddenly turn violent. They also expose the polarised nature of fake news and stardom that we tune into today, reminding us of the dispersed regimes of surveillance which impact our consciousness and bodies at an everyday level.

Figure 3. Ravi Kishan in Hindutva

The Reality Effect of CGI

Even as new borders are being drawn over social media, as a dutiful student of film studies, I must duly warn you that movies do not only create consensus at the level of narratives but also through the use of filmic space, objects, sound, visual tricks and special effects —the apparatus. Let us take an example.

The narrative of the film RRR follows a British officer called Ram and a Gond man called Bheem. Ram is motivated by his father’s participation in the Sepoy Mutiny (and his murder at the hands of the British) to dismantle the British army from within. He has left his village life where his wife Sita waits eagerly. Meanwhile, Bheem has seemingly no connection to the freedom movement. His sole motivation is to rescue a tribal girl from his village who has been kidnapped by the British general.

In a pivotal scene, when Bheem is captured, Ram, to fulfil his duty as an officer has to lash him till he ‘bends the knee’ to the Queen. However, Bheem is shown to be adamant and does not bend. A few sequences later, when Bheem and Ram join hands to defeat the British soldiers, Ram undergoes a process of apotheosis. He is crowned and saved by Bheem and realises his true form as a deity. This is marked by a return to the primitive bow and arrow, with which he kills the entire garrison and rescues the tribal girl. An interesting sequence follows this. Bheem pledges himself to the freedom cause and bends his knee to the divine Ram, asking for his blessings and shiksha. The civilisational process is akin to the one underlined by Savarkar, where he reads not only the Dalits but also the Adivasis who can be assimilated within the idea of a Hindutva nation.2

The rise of the film RRR culminated in a triumph— the winning of The Best Song at the Oscars with Naatu Naatu. What can explain this global moment? Economic flows are changing rapidly to create a globalised marketing of Hindutva. Films like these invite you to think deeply about the transnational box office, the NRI vote bank — the cultural geopolitics of the Hindutva film.

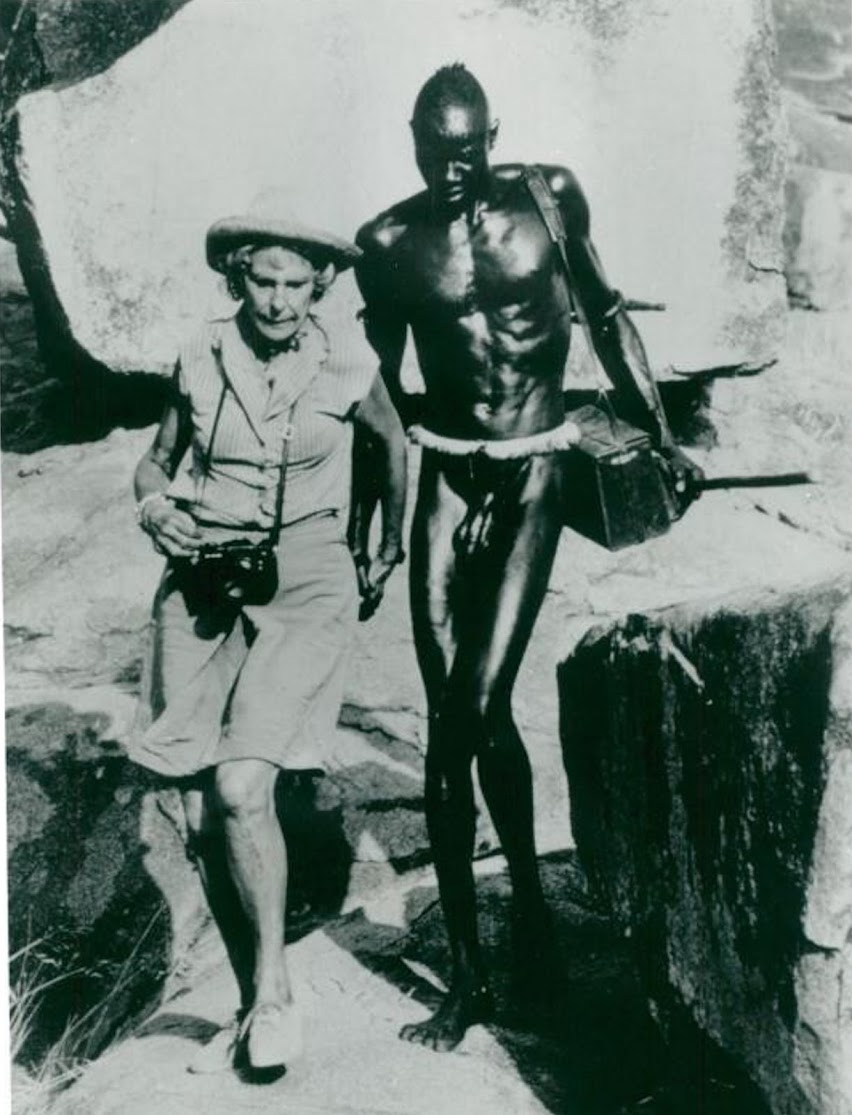

However, beyond narrative, it is through visual effects (VFX) that a scene is framed where Ram’s body metamorphoses from a mere mortal to achieve divinity. It is interesting to note that it is a popular, digital and reproducible technology that is used to bridge the gap between history and myth. Film theorists and critics have endlessly debated the transition from celluloid to digital cinema, with scholars like Lev Manovich noting a quality akin to painting in the latter. Such choreography of visual tectonics alerts us to possible connections with fascist aesthetics that Susan Sontag has explored in Fascinating Fascism.3 Here, she notes the constant emphasis of the camera on creating bodily supremacy and beauty in the Nazi Leni Riefenstahl films like Nubia and Triumph of Will. This optical sculpting of the landscape can take on different dimensions — as in a film like URI, where, Shaunak Sen argues, the desire to possess enemy territory is realised through the use of drone footage.4

A new industry is on the rise, with its wave of CGI artists. From the theatre backdrops by Baburao Painter to the elaborate foreign locations in Switzerland which marked Indian cinema’s history, we have come to companies like NV VFXwaala, supervised by Prashad Sutar, who ran the controversial graphics of Ram in Adipurush. It is backed by funding from Star Power — Ajay Devgn.

Here then, a new world is being dreamed of and sustained. This, however, is not a debate in favour of representational realism and the vilification of VFX or imaginative worlds (utopias and dystopias). In fact, the animated film Sita Sings the Blues by Nina Paley is a sharp commentary and modern retelling using shadow puppets concerning the equal treatment of women and Sita’s cry for justice. Anamika Haksar’s Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Jaa Raha Hu (Taking the Horse to eat Jalebis) uses animation as a Brechtian and magical realist mode to juxtapose the images of riot victims as well as the labouring migrant class of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi) with their unrealised dream sequences (drawn from her ethnographical walks and conversations).

The intention instead is to draw attention to the myriad ways in which new technological and scientific industries have always been historically mobilised to reconfigure age-old religious practices and mythologies in public spheres starting from print culture and lithographs to photography.

The representational desire to deify takes on one such contemporary mode in the genealogy of perception with these Hindutva movies and derives in my opinion from an algorithmic aesthetic logic. However, such technology, as explored above, also lends itself to an ethics and aesthetics of resistance.

Figure 4. Ranbir Kapoor in Brahmastra

The question then in our age of data capitalism is: From what vantage point will we write this social history of labour, graphics and technology?

In 2023, the VFX artist-workers of Marvel voted collectively to unionize. They recognised that the use of such new skills to create fantastical worlds relied predominantly on cruel working conditions and a real fight for workplace rights. On the other hand, a film like Humans In the Loop by Aranya Sahay responds to these disparate worlds and interests. It puts its Adivasi protagonist, a single working mother in rural Jharkhand at the heart of a data labelling centre used for training AI art and language models.

Figure 5. Leni Riefenstahl doing her fieldwork in Sudan with a Nuba person

Conclusion

Where then do we level our activism, as sites of contestation get blurred? What are our sites of resistance? Are they film festivals that are being intensified by corporate infiltration, Hindutva sponsorship and distributors like MUBI? Or are we reliant on messianic figures like Anurag Kashyap?

It is time then to come back to some fundamental provocations. What does a Netflix subscription (of 250 rupees a month) mean? Who are we as consumers and critics of this genre of Hindutva cinema? What kind of neurochemical changes are these ecosystems leading to?

As I write the concluding statements, Samay Raina, the comedian and influencer popular for India’s Got Latent on YouTube, has been charged with vulgarity by the same right-wing ecosystem that had benefited, supported and rewarded him. The polarised opinion among liberal circles stands as this: We hate his misogynistic guts but we will defend to death his right to produce content.

Whose downfalls do we secretly plot, wish for and relish? Our cultural fetishes are structured, and according to a philosopher like Zizek, we willingly buy into these narratives even as we know that these are biased (in a process he calls fetishistic disavowal). We are complicit.

How can this paradox be resolved? One of the texts that I keep coming back to is Ranciere’s discussion on the connection between Aesthetics and Politics in Dissensus. Here, he reiterates that consensus in art is produced through a hierarchical and scientific relationship of cause and effect with politics and vice versa. What is shown as an act on screen must lead to a logical correlation in the world of the film or with reality outside. Instead, he is interested in the zones of collapse (we need to produce dissensus) where this ordering breaks down and a different spatial, visual or other logic re-orders the distribution of these ‘regimes of the sensible.’

In a film like Funny Games by Haneke, such dissensus is awakened through a collapse of the fourth wall to hold the viewer complicit in the kind of enjoyment he gets from violence on screen. In Zone of Interest by Glazer, it is the disjunction between the normalcy of the Nazi household and the sonic landscape of the concentration camp that sets up the dissensus. In a series like Paatal Lok, the police order is disrupted by the narratives of an underclass, even as a detective lays bare the regimes of power (which are well out of his control) at play.

Even as you and I run through the possible answers, it might be fruitful to conclude with the fascinating vocabulary from the Third Cinema manifesto written by Solanas and Getino in the 70s that opens up a possible network of global solidarities that can be developed:

‘The man of the third cinema, be it guerrilla cinema or a film act, with the infinite categories that they contain (film letter, film poem, film essay, film pamphlet, film report, etc.) above all counters the film industry of a cinema of characters with one of the themes, that of individuals with that of masses, that of the author with that of the operative group, one of neocolonial misinformation with one of information, that of passivity with that of aggressions. To an institutionalized cinema, he counterposes a guerrilla cinema; to a cinema made for the old kind of human being, for them, he opposes a cinema fit for a new kind of human being, for what each one of us has the possibility of becoming.’5

Their manifesto remains important for our present:

How do we mobilise culturally, politically, aesthetically?

- Menon, Nivedita. “Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: A New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony.” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no. 24/25, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.6846.

↩︎ - Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar. Essentials of Hindutva. Global Vision Publishing House, 2021.

↩︎ - Sontag, Susan. “Fascinating Fascism.” New York Review of Books, Feb. 1975, campus.albion.edu/gcocks/files/2013/08/Fascinating-Fascism.pdf.

↩︎ - Sen, Shaunak. Digital Events: Crosstalk between Media Forms and Contemporary Hindi Cinema. 2020, Unpublished PhD. ↩︎

- Solanas, Fernando, and Octavio Getino. “TOWARD A THIRD CINEMA.” Cinéaste, vol. 4, no. 3, 1970, pp. 1–10. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41685716.

↩︎