Often, encountering stunning images makes a deeper impact on us than reading stark facts in text. After years of stalled recruitments, legal deadlocks and sustained protests by a section of the deprived candidates for the School Service Commission examination, the pictures of a massive stockpile of cash, recovered from an aide of the erstwhile Education Minister of West Bengal Partha Chatterjee, finally gave a massive jolt to large sections of the people of West Bengal. The fact that financial corruption has seeped into the arteries of the state’s governance under the incumbent Trinamool Congress government has not been unknown to many. However, this public revelation and sustained brutal police crackdown on the protesting deprived candidates cemented an uncontested acceptance of the fact of systematic corruption in the public appointment of a vast swathe of new recruits in schools since 2013. But the larger question that got buried amidst the public furore was how, or why, some cases of financial corruption attract glaring public attention and rage, while others generate neither such wide recognition nor evoke similar levels of disgust. One can ask why concerns regarding disproportionate accumulation of wealth by rich corporates, or the opaque curtain surrounding the PM CARES fund raise a faint murmur of worry among a limited section of the electorate, leaving the rest to be either unaware or not sufficiently concerned. This requires a critical analysis of a few cases of financial corruption in India in the recent past and the patterns which public reactions towards them expose.

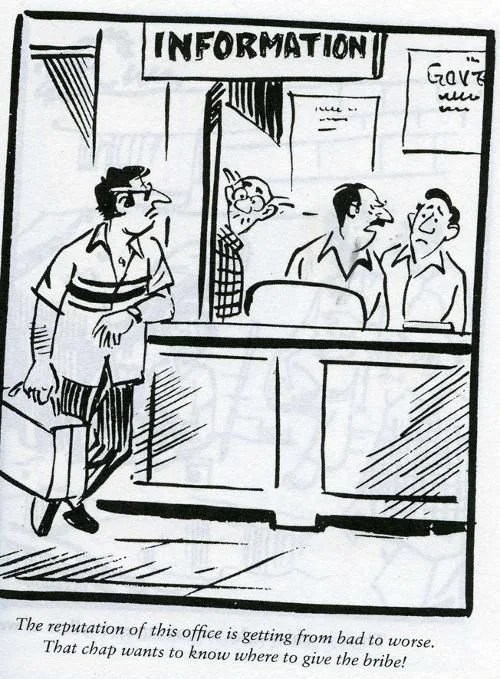

Before probing deeper into questions surrounding the various degrees of outrage regarding cases of corruption, a closer look at a few hard facts and explanatory theories might help us get a grasp on the problem. While the neoliberal system—further entrenched since the 1990s—has accelerated finance capital-based exclusionary growth and commodification of essential public services like health and education, an ailment that is relatively overlooked is the persistence of novel forms of financial corruption at different levels of state-functioning. Even if one were to leave aside the mega-cases of corruption involving mass recruitments against positions for public employment or the exchange of mutual benefits between state functionaries and the big corporates, corruption lingers on at the very micro-level as an everyday phenomenon. According to the Global Corruption Barometer 2020 brought out by Transparency International, India tops the list in Asia in terms of petty bribery rates. Released on the eve of International Anti-Corruption Day, December 9, the Report shows that almost half of those who paid bribes in India were asked to do so as if it were part of the normal procedure, while 32% of those who banked on personal connections claimed that they would not have received essential services if they had not paid bribes in the first place.

This depicts the grim reality but does little to explain the underlying motivations—and limitations—that drive corruption. While there are generalized explanantia like political culture and lack of education that provide only a broad framework, it is the complete breakdown of the principal-agent relation that, to some extent, explains corruption in the Indian context. In a conventional idea of a democratic structure, both public representatives and officials are agents who convert the political will and mandate of the electorate—who are the principals—into reality. However, behind this cloud of democratic idealism is a steep imbalance—between citizens’ role in actual statecraft and the official conduct of the agents—that loosens public scrutiny and undermines institutions and mechanisms that monitor the self-serving actions of the agents. This, in turn, generates an institutionalized culture that normalizes corruption incrementally. Most people, in despair, give in to the negative consequences and supposed irrationality of swimming against the tide, thereby discouraging a lot of individuals from steadfastly insisting on transparent practices on every occasion. This finally leads to a collective-action phenomenon where there are very few exceptionally ethical persons left in the administration. The expectation of honesty and integrity from government personnel then becomes largely non-existent. The principal-agent relation discussed above is further damaged since the percolation of institutionalized corruption among the people results in a scarcity of ethically-sound principals who can keep a check on the conduct of the state officials. Transfer of responsibility, when imperfectly monitored, therefore causes a sustained erosion of accountability and expectations thereof, amongst all stakeholders.

The cases of corruption that directly deprive people of their essential resources are useful for our consideration. The blatant visibility of incidents such as recruitment scams, siphoning off of targeted cash transfers for affordable housing, or relief aid for mitigating the impact of natural disasters instantly gives off the impression of being unfair to a certain group of deserved beneficiaries, and such cases tend to consequently ignite immediate protests. This is in sharp contrast with cases like increasing concentration of the national economic assets in the hands of a few corporate giants, the flight of wilful defaulters from the country after saddling banks with huge Non-Performing Assets (NPAs), or the rigged sale of Public Sector Units (PSUs) including profit-making ones by the central government to private entities. The crafty manoeuvres involved in such cases ensure that large sections of the affected populace do not get to know fully how they are being deceived and affected. This cognitive lag is not bridged if someone instinctively avoids comprehending nuanced and layered controversies and puts more thought into cases of direct injustice meted out to them. For example, one might be enraged more at having to forgo a part of MGNREGA wages to the local political extortionists than at encountering the news of the wealth of Gautam Adani rising astronomically while flouting all norms of corporate governance and public regulation during the years of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this is quite understandable, given that poor people cannot be expected to give up existential concerns surrounding their livelihoods. However, this does not imply that they are unaware of the direct ramifications of such concentration of immense wealth in the hands of big corporates. Neither can we ignore the fact that the different sections of the working class–-bank employees, power sector engineers, rail workers, LIC employees, port workers—have often successfully resisted the large-scale privatization and disinvestment attempts by the NDA government under the garb of the ‘National Monetisation Pipeline’. Millions of factory workers have organized against the dilution of the labour laws which somewhat protected their rights before. The year-long farmers’ protest in 2020-21 also shines as a glowing example of successful mass mobilization against unfair corporate intrusion into agricultural purchase, storage and marketing.

The depredations inflicted by the double-headed force of cronyism and corruption are complemented by the propaganda spread by a large section of the mass media, which, by virtue of being owned by the big corporate houses, toes the line of the establishment. In our times, scrutiny and criticism have been replaced by the amplification of state-sponsored narratives and a dangerous polarization of the space for civic dialogue. The economic misdeeds committed by members of the establishment are either bypassed or shown in a much truncated and diluted form. The intricate and specialized nature of issues such as Defence deals or systematic disinvestment of the PSUs further creates possible difficulties in understanding them holistically. Moreover, the sensationalism associated with investigations by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and Enforcement Directorate (ED) is obviously absent in the cases involving members of the ruling dispensation. Thus, cases like the highly controversial Rafale aircrafts deal escaping a Joint Parliamentary Committee probe despite strong pleas by the opposition, or a former Chief Justice being given a Rajya Sabha nomination—arguably as a reward for delivering a few vital verdicts in favour of the central government—soon after his retirement, has failed to provoke widespread mass discontent.

Similar is the fate of the Right to Information Act. An amendment in 2019 has hamstrung the autonomy of information commissions by enabling the central government to determine the tenures and salaries of all information commissioners, which it was not entitled to do before. Since it came to power in May 2014, the NDA government has not appointed a single commissioner of the Central Information Commission (CIC) without citizens having to move the courts. More recently, the extraordinary situation posed by the Covid-19 pandemic was used as an emergency window to draw up crores of rupees—including enforced contributions from the salaries of government employees—to fill the newly-instituted PM CARES fund. The government, by its own admission before the Delhi High Court, has maintained that the fund corpus is neither under the purview of “the State” nor a “public authority” under the Right to Information Act. Without a CAG audit, the publication of expenditure reports on its own website does little to dispel the glaring lack of accountability on part of the major stakeholders of the fund. Attempting to situate the present state of India in its larger historical and comparative context, scholars like Ashutosh Varshney have emphasized the ‘democratic backsliding’ we are undergoing, as opposed to a singular democratic collapse through coups or suspension of elections and prohibition of opposition political parties. As corruption in its varied combinations and complexities continues to nibble at the edifice of Indian democracy, a willingness on the part of the people to think critically about these subjects is a useful opening nudge. Amidst concerted attempts to hollow out existing institutional safeguards and to disempower a citizenry sinking further in economic distress, the festering cancer of corruption despairingly awaits urgent treatment.

One thought on “Corruption Conundrum: The Political Anatomy of a Pecuniary Problem—Ritabrata Chakraborty”