A typical scene in Kashmir invokes in our mind lush green forests, snow clad mountains, a calm Dal lake. The notion of a picturesque Kashmir, that is romanticised, dominates our understanding of the place. Any kind of violence that occasionally springs up in media reports is represented as a kind of break in the continuity of ‘peace’ and beauty within the region. We have in our perception of the region formed a ‘paradise’ that is Kashmir. How utopic is the vision that we seek to impose on our understanding of Kashmir?

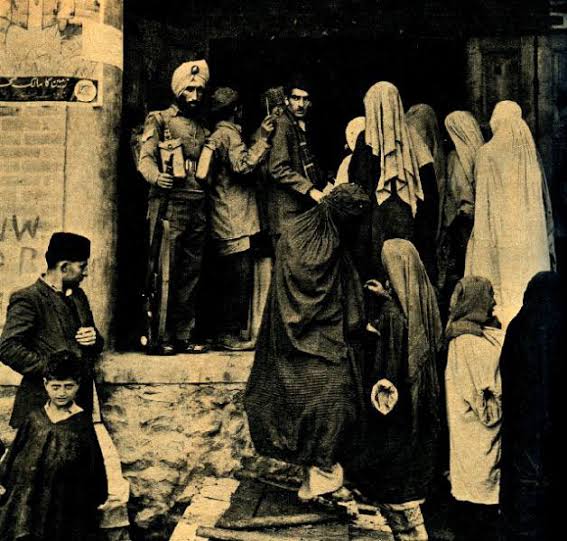

The romanticism attached to Kashmir as a paradise has long been manifested in popular culture. The mainstream Bollywood industry has used it as a ‘background’ and ‘scenery’ to unfurl romantic musings of heroes and heroines. What needs to be observed here is that almost in all such depictions, the presence of Kashmir’s own people is completely obliterated. Even when they are included, Kashmiris are depicted objectively in hyperboles to further accentuate the beauty of the landscape. They are presented in their elaborate indigenous dresses to exotify the scenery, removing it further from any real conception of life over there.

Kashmir in all its scenic beauty is primarily a landscape, a tabula rasa wherein we, as outsiders, impose our fantasies, an imaginary sense of nostalgia and our perception of an escape into a ‘pure’ area. Kashmir is seen as a land to project one’s own subjectivity while side-lining other experiences. Popular perception of Kashmir as a land of scenic beauty removes it from reality. Kashmir is viewed primarily as a land, devoid of its own people. As a result, human feelings and emotions of Kashmiris completely escape our understanding. The reification of Kashmir as a landscape objectifies the land along with its people. It is mouldable and designed to suitably cater to our desires. Questions of ownership over Kashmir come into the fore as it is seen as an object, a land that can be appropriated. Perceived purely as a geographical entity, the Kashmiris and their own desires are conveniently side-lined and their right to self- determination ignored.

The tendency of removing the Kashmiris and ignoring their subjective realities from the region has conveniently subsumed their own desires of self-determination. Hence, the ideal notion of Kashmir in our minds gets disturbed when this subsumption is questioned by them. Indignations, protests, declarations of freedom from subjugation, armed resistance is seen as ‘unrest’, a deviation from the norm of ideal plane. These are simply irritants that have to be ‘controlled’ to bring back the ‘original’, so called nostalgic idea of a paradise.

A case study explores the Hanjis who have lived around the Dal Lake for generations and whose livelihood as fishermen, houseboat owners and farmers have been dependent on the Lake. Intense development of motor roadways by the government has restricted their access to the area close to the Lake. The Hanjis’ use of the Lake made them the target in face of environmental restoration, which had disturbed the ‘pristine waters. Government interventions bent on restoring the ‘pure water body’ ignored the complex ecology of the Lake and most importantly of the livelihood of the community that had depended on this source for generations. They were perceived in popular imagination as encroachers who had disturbed the pure waters. The question of conservation, masked in an apolitical agenda, expanded the state’s authoritative influence by stripping the Hanjis of their political and residential rights on the Lake, thereby establishing greater control and assertion of power. Thus, as Michael Goldman theorises, ‘green neoliberalism’ as is used by a capitalist state to integrate such local ecologies into the global tourist economy, makes its way into the Indian State’s strategy for strengthening itself in Kashmir through violent and repressive control. That is not to say however that Kashmiris’ claims to azadi and environmentalism have never converged or are contradictory. Kahmiris, by themselves had undertaken several initiatives and methods of conserving their own homeland. In 2013, Kashmiris decided among themselves to use bicycles to demonstrate their responsibility towards nature and in a way to reclaim alleys and pathways that had been militarized and occupied. Many Kashmiris like Aftab Qadri themselves joined hands for the conservation of the Dal Lake while simultaneously demanding azadi. Qadri argued, “‘If you give the impression that life can thrive under a military occupation, that people can focus on their surroundings, their environment, you are relegating the freedom struggle to the background; you are marginalizing the struggle for Kashmir’s azadi.’’

One cannot ignore the obvious commodification of nature that occurs systematically in any capitalist economy. The region of Kashmir too, is systematically commodified in the name of promoting and developing tourism. As claims to azadi by Kashmiris creating ‘unrest’ would hinder the intensification of tourism here, they are showed by the Government to be antagonistic of objectives. For the sake of extraction through a thriving tourism economy, control by the State is then justified through authoritarian interventions.

The stifling of self-determinist claims by the ongoing communication blackout is again justified as a method to exert control so as to ‘restore’ peace and bring the notion of Paradise back again. The assertion of the “others’” desires are trumped by the development narrative. “J&K and Ladakh have the potential to be the biggest tourist hub. Remember, there was a time when Kashmir was the favourite destination of Bollywood filmmakers. In the future, I am confident that films, regional and global, will be filmed in J&K,” Modi explains. Ironically, the Indian State has been responsible for the killings of uncountable people in the valley as well. Reportedly, there are over 6000 unmarked graves in Kashmir. The ongoing communication blackout has claimed 17 Kashmiris on account of pellet gun firings and has left 6221 injured.

What needs to be identified and acknowledged by us in not just the scenic beauty and imagined idyllic sate of nature in Kashmir. Landscapes do not exist in isolation from their own people. Landscapes vary and change according to their own situations and colours. Imposition of a separate, non-human identity to a piece of land, alienates its own people from their homeland. The land is of the Kashmiris and their claims to self-determination cannot be marginalized in an attempt to recreate our imagined sense of an elusive utopia.

honestly and unbiased, a lucid write up .except a few, Indian media are suppressing the ground level realities in Kashmir.not only suppression of facts, they are focussing an utopian happy feelings of the people of Kashmir.At least, this reported , exposed the present scenario.

LikeLike