The mass media, considered the fourth pillar of democracy, exists today amidst total frenzy. It has been hollowed by noise, insignificant debates, emotional appeals, and distorted facts and has abandoned its responsibilities as watchdog, social critic, navigator of information, and, most importantly, shaper of discernible public opinion. The media’s reliance on huge corporate houses and conglomerates for funding have crippled it, forcing it to resort to advertisements and turning it into a vehicle for the market ideology, which treats people merely as consumers. The situation exacerbates as the cult of the personality triumphs over the logic of policy and the media starts promoting certain ideologies, thereby enabling demagogues to achieve narrow political gains. In an era wherein information is easily accessible and comes from various sources, including social media and instant messaging platforms like Twitter and WhatsApp, consumers are not only misled and deceived but are also discouraged to pay for obtaining news from credible sources. The media has become so entangled in this dead-lock that it prevents us from seeing it as the cause for its deplorable condition in spite of its predominant role in manufacturing fake news and with it, consent.

Information is more easily available today than ever before. However, this ease does not come with the promise of accuracy. Facts are tampered with and distorted according to the interests of the individuals presenting them and in such a manner that people simply accept them without question. This gullibility creates a separate virtual world which is far from reality and channelizes people’s emotions to create biased perceptions, obliterating their critical faculties. Furthermore, social media also facilitates direct confrontation between the groups created through reaffirmed prejudices and spread of hatred, leaving this its creative potential in an abysmal state. One has to acknowledge that social media has brought to light certain important issues, the #MeToo movement being a recent example, which means that the problem lies not with social media itself but with the irresponsible manner in which it is used. For instance, a teenager sitting in the small neglected town of Veles in the Balkans, where the average monthly salary is $371, earned an easy $16000 by generating misleading news during the 2016 US presidential election, unaware of the ramifications of his actions in the country, where ‘fake news’ is credited to have increased Trump’s support base by 4%.

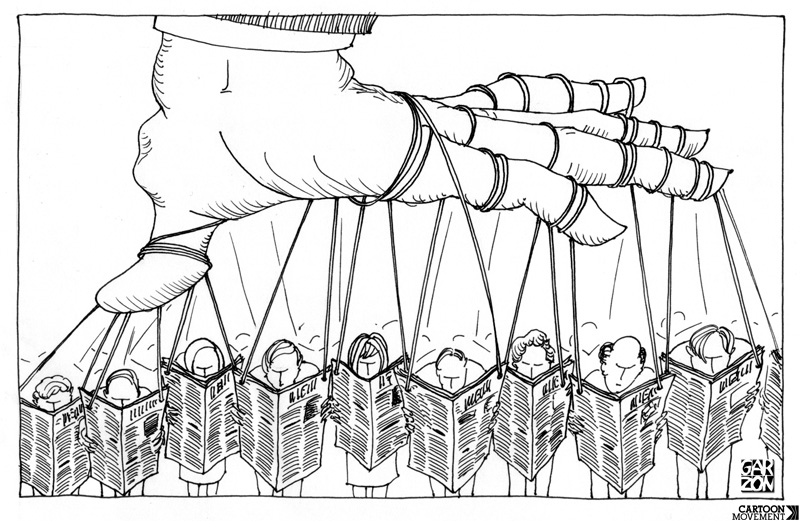

These subtle changes have made accurate journalism an increasingly challenging endeavour, with public trust in the media being at an all-time low and expressions such as ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth politics’ becoming increasingly popular. Chomsky’s remark, “The population doesn’t even know what it doesn’t know” rings truer now than ever before. It highlights the pervasiveness of the propaganda model, in which the media serves and promotes the interests of the powerful corporate entities that control and finance it. The representatives of these interests have important agenda and principles that they want to advance and they are well-positioned to shape and constrain media policy, which ultimately corrupts the media and deviates it from its duties. The strengthening of this model has weakened the public sphere – when, ideally, matters important to a democratic community should be debated and information relevant for an intelligent citizen should be provided, the media houses attempt to reinvent reality as it suits them. The use of propaganda in media as it has arisen in this ‘post-fact’ age is not specific to a spatio-temporal context. Throughout history we have seen this recurring, be it in the United States’ portrayal of the Iraq invasion or in the depiction of web brigades who fuel the anti-Ukrainian hysteria and prop up Putin’s falling approval rating or in the whitewashed presentation of Indonesian attacks on East Timor. It all becomes a part of the strategically organised chaos, and sadly, India is not left out in this race!

Former BJP Minister Arun Shourie compares the current state of the Indian media with that of North Korea, where all one can hear is praise of the beloved leader, not only hinting at the presence of ‘embedded journalism’ or the ‘Godi media’ as Ravish Kumar calls it, but also giving a glimpse of the fascist tendencies in the world’s largest democracy. One could skim through every news channel and all one would see is a single face and hear a single name, a name striving to become the sole identity of a diverse nation like India. The process of turning a citizen into hypnotized follower becomes apparent as we see ourselves being relegated to the position of puppets enthralled by toxic ideologies, with the media acting as catalyst. The recent ‘Operation 136’ conducted by Cobrapost revealed the propensity of media houses to strike business deals to promote the ‘Hindutva’ agenda and help polarise voters in the run up to the 2019 elections. Later, certain video recordings were published showing managers and owners of some of the largest newspapers and T.V channels succumbing to the same package of ‘Hindutva’ advertorials. More than two dozen news organisation were willing to not only cause communal disharmony and create bigotry among citizens, but also tilt the electoral outcome in favour of a particular party for a price. This unscrupulous behaviour gives an insight into the current state of the media and explains how its greed has polarised political discourse and caused communal tension, which is now threatening India’s secular fabric.

The media’s excessive emphasis on certain issues and indifference towards others, as a result of wearing sponsored blinkers, demands our attention. Noisy vitriolic debates have become a staple on major news channels, along with flashy headlines and never-ending advertisements. The media lacks inclusivity and equal representation in news-coverage. While 70 per cent of India’s population is directly or indirectly related to agriculture, the media coverage devoted to it is less than 4 per cent, attention to rural areas being limited only to accidents, natural calamities, and crimes and hardly reflecting the real issues that trouble the majority of the nation. Over 3,10,000 cases of farmer suicide have been recorded since 1995. The government and media’s response to this crisis has so far remained negligible. In fact, not very long ago, when the country experienced a historic ‘Andolan’—the Kisan Mukti March, which witnessed about a lakh farmer along with other supporters congregating in the capital and demanding their rights, hardly any mainstream media covered it. Peddling lies and spreading jingoism seems to have become the primary function of the Indian media at large.

When almost everyone is seen succumbing to the system, the few remaining voices of dissent and subversion are suppressed and threatened. Any line of thought which critiques the present system is discredited and is met with a lot of flak online and violent threats in reality: the unsolved murder case of journalist Gauri Lankesh is not much of an enigma. She was a critic of right-wing Hindu extremism and caste-based discrimination, and a women’s rights activist who had a defamation lawsuit filed against her by certain BJP leaders for writing an article which questioned their involvement in certain malpractices. Her death was not a message to the mainstream media but to the courageous speakers who continue to speak truth to power against all odds. The list of murders of this kind neither begins with Gauri nor ends with her and it not only includes journalists, but also RTI activists and individuals who don’t attract much attention like the former group but are doing the same job as them – holding the powerful accountable and demanding transparency. With an atmosphere of growing impunity, individuals and groups commit violent attacks, including mob-lynching and assassinations, aiming to instil fear in those who dissent and dare to ask questions. It is amusing how questioning those whom we are entitled to question has become a daring act in a democratic country. Siddhartha Deb correctly pointed out in his essay in the Columbia Journalism Review,” Sometimes, it appears as if the enemy is information itself, along with transparency, exposure, critical thinking that might be seen as a characteristic of a free, open society.” This descending trajectory of the media and democracy in India demands an awakening of the whole nation, for re-establishment of the relation between media and democracy and understanding the choice of the former in strengthening or destroying the latter.

Noam Chomsky writes, “It remains a central truth that democratic politics requires a democratization of information sources and a more democratic media”. Besides trying to control and reverse the growing centralization of the mainstream media, grassroots movements and intermediate groups that represent a large number of ordinary citizens should put much more energy and money into creating and supporting their own media. Honest and independent journalism is required now more than ever, when everyone seems to be driven in a herd and few try to step out and ask the right questions. The editor of the Indian Express, Raj Kamal Jha remarks, “It’s not that good journalism is dying, it’s just that bad journalism is making a lot of noise.” Presently, there are certain forums which don’t hold back such as The Wire, a news website founded by the Foundation for Independent Journalism, an Indian non-profit company which is not funded by conglomerates. It has published articles aimed at exposing political scandals, which include the pieces such as The Cobrapost Sting, The Robert Vadra case, and The Golden Touch of Jay Amit Shah. Journalist Palagummi Sainath focuses on social and economic inequalities, rural affairs, poverty and the aftermath of globalization in India. He is also the founder of an online news platform called the People’s Archive of Rural India, which aspires to chronicle the ‘ordinary lives of ordinary people’. Ultimately, the burden of responsibility lies with citizens, who must learn to tolerate different views and see through the illusion of a perfect world created by their leaders. We must engage, enquire, search, question, and acquire epistemic vigilance, so that the power remains where it must reside, that is with the people.

In light of the above discussion, one wonders what the future of the media is and how can it retain its relevance in this changing social and political climate? How does the media’s functioning affect democracy? Is traditional media losing its relevance in a ‘post-truth’ age and is the diligence and journalistic integrity of mainstream media being sacrificed in favour of click-bait, sensationalised stories? However, whether it be the squalor of slums or the plight of farmers, political inaction or prioritising needs of a nation, the issue of caste or manual scavenging, troubling oneself with these questions doesn’t matter when we can settle with much easier questions like “Which mangoes do you like to eat?” or “How many hours do you sleep?” Let us all ponder over it!

One thought on “Amidst the Squealers: The Media in the Democratic Circus—Riya Lohia”