The Sankrityayan Kosambi Study Circle owes its name and inspiration to two of the most remarkable individuals in the history of modern India, Rahul Sankrityayan and D.D. Kosambi. Any biography of either of them would run into the immediate obstacle of classifying their professions, for the scope of their lives’ work is truly interdisciplinary. The range of subjects with which they had dealt, the wide array of languages in which they spoke and worked, and the incredible geographical, social, and cultural breadth of their explorations present both a challenge to the set notions by which we order our lives and an inspiration to imagination and critical inquiry. The idea of the Study Circle was inspired as much by the all-embracing and cosmopolitan character of their lives as by their empathy for the oppressed and marginalized and commitment towards a free, equal, and just society.

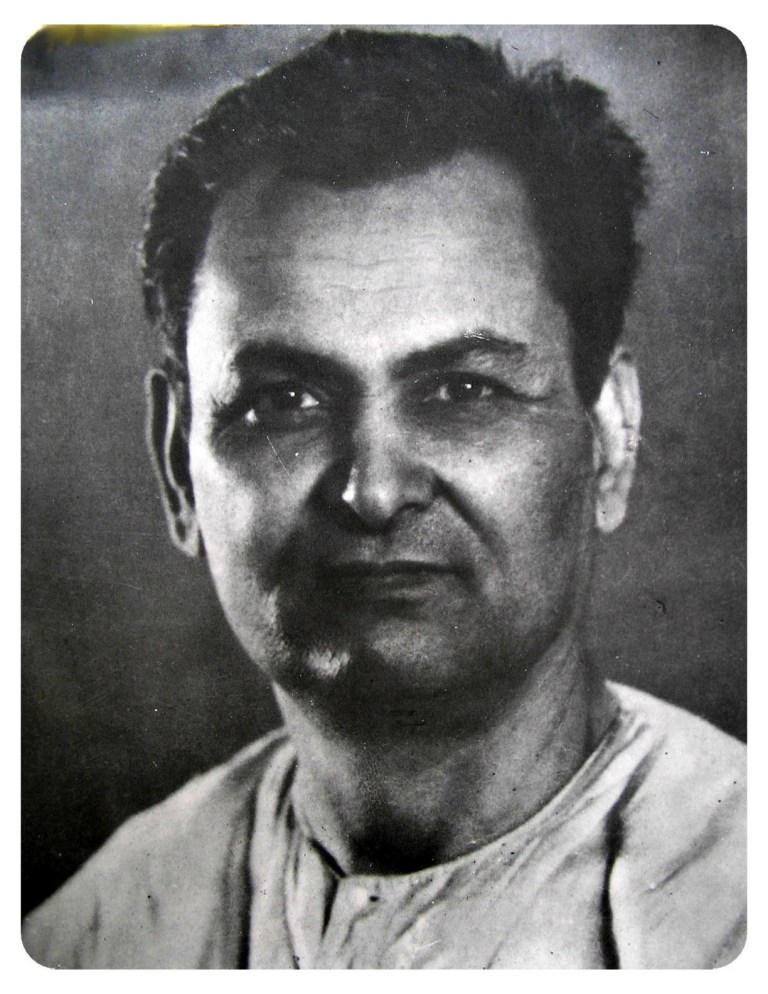

Rahul Sankrityayan (9 April 1883 – 14 April 1963) was born in a small village in Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh. His early life was fraught with dissatisfaction with the intellectual resources and discourses available to him at the time and was marked by a constant search for a rational, humanist perspective of the world. As a teenager he left home to go to Varanasi, where he learnt Sanskrit and later joined a Hindu monastic order in Bihar. His disaffection with the dogma and ritualism of orthodox Hinduism led him to join the Hindu reformist movement Arya Samaj, which too, however, proved stifling to the freethinker that Sankrityayan was. The first major break in this series of forays came with his engagement with Buddhism in 1926 in Sri Lanka, where he lived for several years, studying Pali and working on translating and restoring Buddhist texts. His fascination with Buddhism took him to Tibet, which he went on to visit four times during his lifetime and where he learnt Tibetan, going on to create a Tibetan – Hindi dictionary. His work is significant for the comprehensive picture it gives of the way Hinduism and Buddhism had interacted with each other historically. He eventually eschewed all spirituality and religious belief and became a Marxist.

Sankrityayan’s extensive intellectual discovery owed a great deal to his insatiable wanderlust and flair for languages. A self-described ‘ghumakkad’, Sankrityayan travelled, besides various parts of India, to Nepal, Tibet, Sri Lanka, China, Iran, and the former Soviet Union. He was well-versed in several South-Asian and European languages and wrote on an extraordinary number of subjects, ranging from grammar to politics. Over the course of his travels, Sankrityayan produced numerous accounts of the various landscapes, people, and cultures he had come across and wrote treatises on their histories, especially drawing links between Central Asia and India. His work is the more groundbreaking for having been written largely for a Hindi audience which had almost no exposure to these subjects. He is perhaps best known today for having pioneered travel writing in Hindi and for his novel Volga Se Ganga.

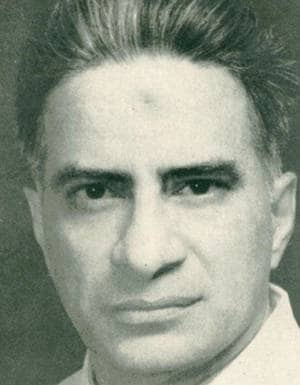

Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi (31 July 1907 – 29 June 1966) was born in Kosben, Goa. The interdisciplinary nature of his academic work cannot be overstated, considering the pivotal contributions he made to disciplines considered as far apart as mathematics and ancient Indian history. Over an entire lifetime of having taught mathematics, he did research in the fields of, among others, Path Geometry and Tensor Analysis and developed the Kosambi Map Function, which is widely used in the study of genetics. He held teaching positions at a number of Indian institutions, including Fergusson College Pune, where his egalitarian ethos clashed with a hierarchical Indian culture which did not value research as highly as he did. This element of being at odds with his surroundings continued wherever he worked and he, like Sankrityayan, was never truly at home in the spaces available to him as a freethinker in twentieth century India. He was extremely active in the international sphere and was a UNESCO fellow to the UK and USA for electronic calculating machine research. He held visiting professorships at Chicago and later at Princeton, where he had extensive discussions with Einstein.

Kosambi’s enagement with ancient Indian history perhaps followed as much from his personal background as from the characteristic problem-solving approach he employed in his work. His work in mathematics required him to learn statistics, which he did through setting himself practical problems to solve. One of these problems was a statistical study of the weights of ancient punch-marked coins, which, along with his other articles on numismatics, was later published in the volume Indian Numismatics. The study of these old coins led him to inquire about the kings who had issued them and prompted an extensive study of ancient records, which required some mastery over Sanskrit. In order to enhance his exisiting knowledge of Sanskrit, which he had inevitably come to acquire from his father, the Buddhist scholar Dharmananda Damodar Kosambi, he turned to studying Sanskrit literature, which lead him to text criticism and Indology. He insisted on regarding Sanskrit texts and ancient myths as sources of data for understanding social and cultural life rather than as sacred works beyond analysis. He brought a paradigm shift to the study of ancient India, and indeed of all Indian history, with his redefinition of the nature and scope of history. Kosambi dismantled the fixed notions of periodisation – ancient, medieval, and modern – and emphasized supplementing literary sources with archaeology, anthropology, and a suitable historical perspective and undertook extensive fieldwork himself. His introduction of the Marxist methodology to Indian history-writing was praised by some and denounced by others as ‘alien’.

The Sankrityayan Kosambi Study Circle was created to provide a platform for dialogue on the intellectual and social legacy left behind by Sankrityayan and Kosambi, and on the wide-ranging issues with which they were concerned and which are of great relevance even today. It needs to be emphasised here that the Study Circle is meant not solely to engage with the particulars of Sankrityayan and Kosambi’s work but is informed more generally by the spirit of diversity and inquisitiveness which they embodied. It hopes to create a space for having meaningful conversations about social, cultural, and political issues pertaining to India to which individuals are able to bring their own unique interests, voices, and perspectives. Lokayata, the Study Circle’s official blog, is an attempt to create such a space. The record of work left behind by Sankrityayan, who only received schooling till middle school, and Kosambi, who despite having been formally trained only in mathematics contributed to numerous other disciplines, constantly unsettle our preoccupation with academic degrees and conventional disciplinary boundaries. The Study Circle was inspired by the conviction that knowledge can come from myriad sources and in various forms and hopes to facilitate discourse across disciplinary divides. Among the other things common to Sankrityayan and Kosambi was the centrality of activism to their lives, which both enriched and was reinforced by their intellectual endeavours. Sankrityayan was imprisoned several times during his life for his political activism, including in the 1920s for his participation in the Non-Cooperation Movement and later for taking part in the Kisan Sabha Movement in Bihar. Kosambi’s life was governed as much by passion for mathematics and the study of ancient India as it was by his commitment to the preservation of peace and in 1955, he headed the Indian delegation to the World Peace Conference at Helsinki, Finland. The Sankrityayan Kosambi Study Circle was created with a firm belief in the mutual dependence of theory and praxis, and of the need for recognizing and solidarizing against inequality, violence, and injustice in all their forms. It seeks to contribute, through discourse and direct action, to popular movements struggling to create a better world.